Narrative Driven Development

As human beings we are all experiencing a first-person narrative. We are experiencing the events of our day and our lives playing out from our point of view. In our jobs as software engineers, however, we encounter many other narratives.

For example there’s the story of the projects we are working on, the teams we are part of, the companies we join or work with. There’s a bug we are investigating, the tools we are using, the codebase we are developing. All of these things have narratives of their own which are playing out over time.

A crucial skill as a professional is jumping from narrative to narrative quickly and efficiently, inhabiting this other story temporarily so that we can make good objective judgments as to how to best advance it.

Effectively and efficiently surfing from one narrative to the next is one of the most important non-technical skills a software engineer can cultivate. It’s not a question of being robotic or dispassionate, it’s great to bring our own enthusiasm and flair to problems, but you must always keep in mind the two are separate.

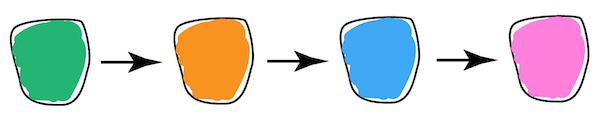

Narrative Orthogonality

The narratives in our work worlds are not always positive and hopeful. Sometimes they are frustrating, confusing, or bleak. The good thing is that narratives are often independent of each other. I can be tending a dumpster fire one minute, while killing it on some other project the next. And I can leave both of these narratives suspended at the end of the day, and not let them invade my life at home.

We ruin narrative independence if we bring too much of our own mood into each situation. If you are having trouble keeping narratives separate, you might need to debug yourself rather than your code. Experiment with sleep, diet, exercise, and spending time on relationships. Ask for help if needed.

As an example of narrative independence, suppose your company is falling apart, you can still be super excited about the specific technical work you are doing. Or about your own career, since you are likely in the process of looking for a new job.

In the other direction, if your eyes are bleeding from a difficult bug, you can still be excited about the team’s progress, the company or your profession. It’s exactly these larger narratives that can motivate and recharge you when times are tough.

The Craftsman Narrative

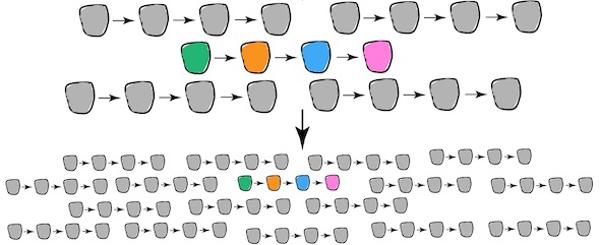

An iconic narrative of software engineering is someone hunched over their keyboard editing text. My text editor, my keyboard, and my screen are all expertly engineered artifacts designed to make the editing process pleasant, effective, and efficient.

Editing text is a physical act. Hands flit over the keys, or depending on your personal style they pound the keys into submission. Either way, it’s a kinesthetic dance with rhythm and flair. I can perform this dance pretty much whenever I want, no matter what else is happening around me, it’s a respite from everything.

Craftsmen throughout history have used their hands to work leather, iron, or wood. We think of our software jobs as purely intellectual, but there is a substantial physical element, just as their jobs had intellectual components.

But then they got down to the business of shaping matter, the business of making noise. With our mechanical keyboards, we can make plenty of noise as well. I’m going out back to the shop for a while to bang on the keys and clear my head.

Trend Spotting

Most of the time switching narratives does not itself solve problems. We still have to fix the bug, write the documentation, or work out the design. The problem will usually be waiting for us when we return.

But switching narratives has often given me a different perspective. It can be both comforting and eye-opening to temporarily inhabit a different headspace. When you switch narratives, take some time to really load it up into your mind.

Who are the players, what has been happening in the story so far, where does it look like things are going? I try to use my whole self, not just my technical skills. You should nurture your intuition and instincts, they are some of the things your brain does best.

Switching narratives has helped me spot trends and patterns and come up with ideas others have missed. The most impactful decisions or contributions I’ve made in my career were the result of considering things from a different point of view, or on a different time scale.

Learning

Sometimes it’s not enough to switch narratives, you want to reframe the one you are in. A common reframing for me is seeing the frustrating or difficult experience I’m enduring as learning. That usually changes my feelings immediately.

Learning is a powerful narrative in software engineering; it’s something we have to do constantly. We need to learn algorithms, data structures, programming languages, APIs, third-party libraries, tools, the design of our own software, the traits of our teammates, the customer requirements. It’s endless.

In some ways, software development is really just an exercise in knowledge acquisition. Suppose you have a team that cranked on some problem for a year, would you rather keep the software they wrote and lose the team, or keep the team and lose the code? In many cases, I’d much rather keep the team.

Once in a while I’ll accidentally blow away a change, I’ll lose a few hours of work. I’m always amazed when I rewrite it, how it takes a fraction of the time and how the new version is markedly better. What I learned writing the code the first time was more valuable than the code itself.

False Narratives

False narratives are a major problem. If we think we’re in a narrative, but we’re not, our judgments about the present and our predictions about the future could be totally wrong.

Conspiracy theories are one type of false narrative. Conspiracy theories are insidious and destructive. They lead their followers into making an endless stream of bad choices and judgments, poisoning the water for everyone.

A conspiracy theory in software engineering might be something like “there’s a bug in the compiler” or “the database is flakey” or “the other team is out to get us”. Not that these things are never true, but if you explain away a problem by waving your hand vaguely at something else, you are forgoing an opportunity to find out the truth and learn something.

Another false narrative is thinking I’m an expert and therefore things should be easy. I think the better narrative for an “expert” is someone who with patience, time and effort can solve difficult problems.

An expert furniture maker requires many hours to produce a beautiful piece of furniture. They are an expert because they can consistently put in the lengthy effort required to produce high-quality output, not because they whip through it fast, not because it’s become easy for them.

Decision Maker

Another false narrative about experts is they always make the right decision. I prefer to strive to be a good decision-maker more than someone who always makes “good decisions”.

A quick, light, decisive decision-making process is essential because you will need to make hundreds of decisions every day. Almost every code change is the result of some decision. The thing to realize is most decisions are two-way doors, the cost to reverse the decision is modest. But if you agonize over decisions that could be disastrous, even if you make the right call in the end. In basketball, you often need to decide whether to shoot or pass. Either option is vastly better than hesitating and losing the ball.

On the other hand, if you are faced with a tough decision that you can’t make quickly, figure out what new information you need in order to make the decision, then obtain that information quickly. Whether it requires research, finding help, or doing an experiment, a good decision-maker time boxes acquiring the necessary information then pulls the trigger.

Personal Narrative

None of this is to say our own personal narrative does not matter, or the personal narratives of our friends and co-workers. In fact, the game here is the same, we need to strive to always be aware of these other points of view, and then turn our full attention to them at times.

When then pandemic struck and people lost the casual in-person interactions of the physical workplace, there was a real struggle as to how to replace those informal interactions with something that worked online.

The resulting video encounters sometimes felt stilted, but they were essential. I think establishing and preserving a human connection in online interactions is in its infancy, and it’s something I hope we get better at a species as the years go on.

Contain Multitudes

Writing prose in English is also something I’ve gained a lot of experience with over the years. However here again “expert” doesn’t mean getting it right the first time; it means slowly hammering it into shape over time.

I’ve written articles for Wikipedia and seen people sweep through contributing small single-purpose edits. Each editor has has their own point of view. Each editor spots a different problem.

When I edit I try to be all of those editors. Every pass through I find a different small problem. One of the most satisfying experiences is reading all the way through and not noticing any rough edges. Did I miss something? Read it once more. Nothing stands out; now we are getting somewhere.

Doing this with code in particular is kind of magical. As I read it line by line everything seems well-factored and well-named. I can visualize exactly how the code will execute. Nothing is ever fully done, but I’m done with it. I’m ready to move on to something else. I’ve created something of lasting value. Now that’s a narrative with a happy ending.